Middle School Math Students Think on Their Feet

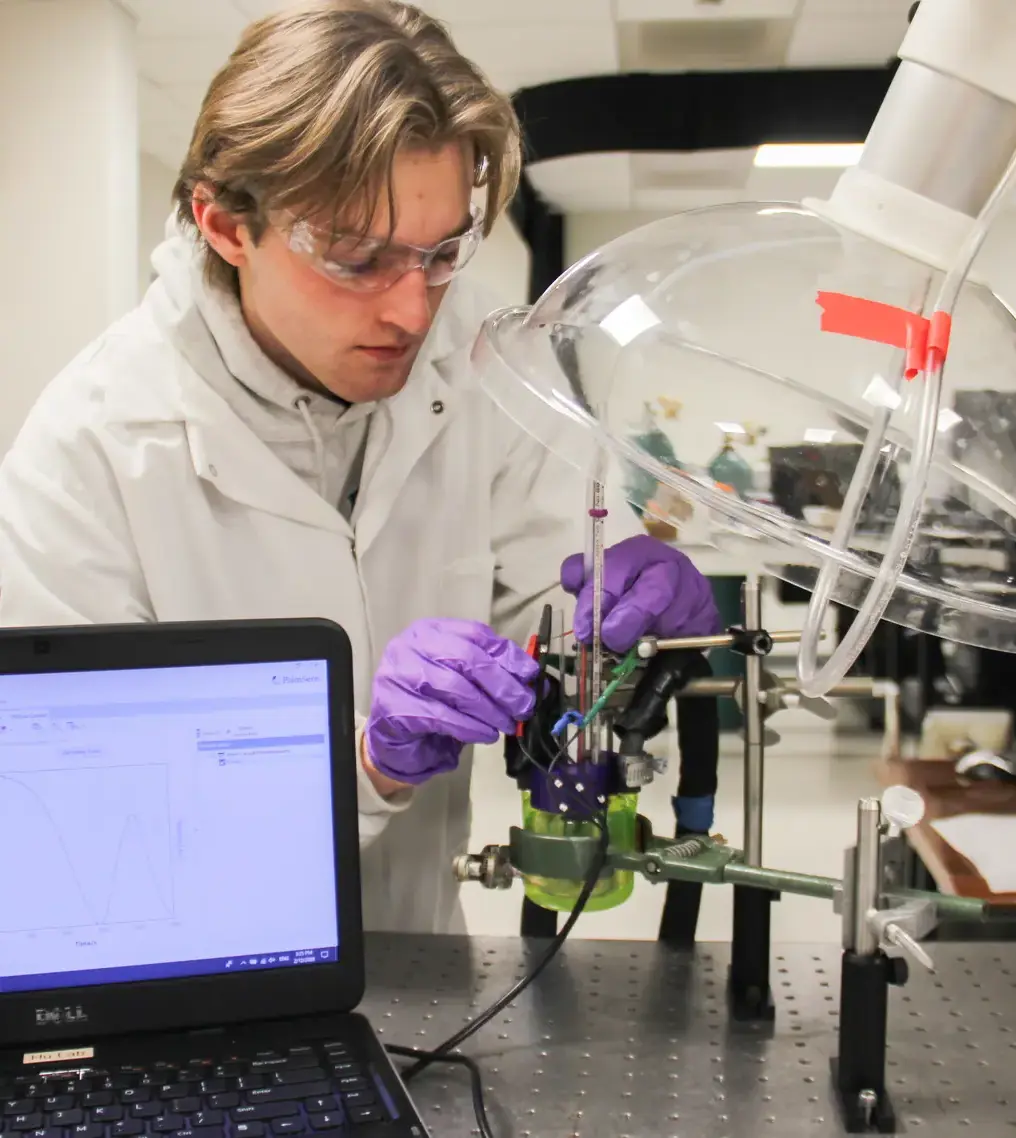

Walk into a sixth-grade math class at King, and you’ll likely find students standing at whiteboards, working in small, randomly assigned groups to tackle challenging math problems. The approach, known as the “Thinking Classroom,” empowers students to take ownership of their learning while making their reasoning transparent to peers and teachers alike.

After exploring the teaching method at a math conference in New Hampshire, teacher Michael Florio was drawn to its focus on student reasoning and problem-solving. He began adapting it for his middle school classes last year, creating an environment where students can struggle, make mistakes, problem-solve together, and learn from one another. Florio circulates the room, asking guiding questions and helping students connect ideas, while deliberately stepping back to let independent thinking flourish.

“By working on the vertical whiteboards, students are able to see everyone else’s work,” Florio said. “We are all learning from each other. If they are stuck, they can walk around and ask questions of other groups. It also lets me see everyone's work at once, so I know if I need to clarify or fix anything.”

The Thinking Classroom approach relies on 14 evidence-based practices that guide how tasks are introduced, how students organize themselves, and how teachers support learning. While originally developed for math, its principles of exploration, discussion, and visible thinking can be applied across subjects, from science and engineering to social studies.

For Florio’s students, the shift has been dramatic. Instead of passively watching a teacher solve problems, they tackle scaffolded “Thinking Tasks” at the boards, building on prior knowledge to solve increasingly complex problems.

“In Mr. Florio’s math class, working on whiteboards really gives me a good visual of the math problems, and I feel more confident, and engaged in the material,” said Ahana Hooda ’32. “I also love the fact that I can easily erase and fix my mistakes so that I can get to try new methods freely.”

Randomized groupings help students work with different peers, learning to navigate various problem-solving styles.

“I never know who will have an epiphany or see things differently,” Florio said. “If I chose the groups, I would be shaping the learning outcome. This way, students take responsibility for their own learning.”

Now in his second year using the approach, Florio continues to refine it, expanding the number of whiteboards and breaking lessons into smaller, scaffolded tasks that guide students step by step. At the same time, he is deepening his own understanding of the model through professional development, conferences, and continued research, bringing new insights and strategies back into the classroom.

The results, he said, have been striking. Students are more willing to tackle challenging problems, discuss ideas openly, and take risks without fear of being wrong. Even students who previously disliked math are becoming more engaged, often discussing their work with excitement at home.

“They are more confident, collaborative, and willing to show their mistakes,” Florio said. “They write more thoughtful reflections on their thinking, and many enjoy the process of solving problems together. The approach has made math class a place where taking risks and exploring ideas is celebrated.